This report was prepared by Weldon Bosworth, Ph.D. on behalf of New Hampshire Wildlife Coalition and submitted as testimony to the New Hampshire Fish and Game Commission on March 19, 2020. Download the full report.

This analysis of the fisher population presents evidence that supports a decision that the season for fisher should be closed.

This evidence includes:

As part of this analysis, the relevance of what was termed an “uptick” in fisher CPUE in 2019 at a previous Commission hearing is put into statistical perspective. Additionally, a cautionary note on how failure to act now by closing the fisher season is one step further along a path where the negative consequences of making wildlife management decisions within the context of a shifting baseline become a reality.

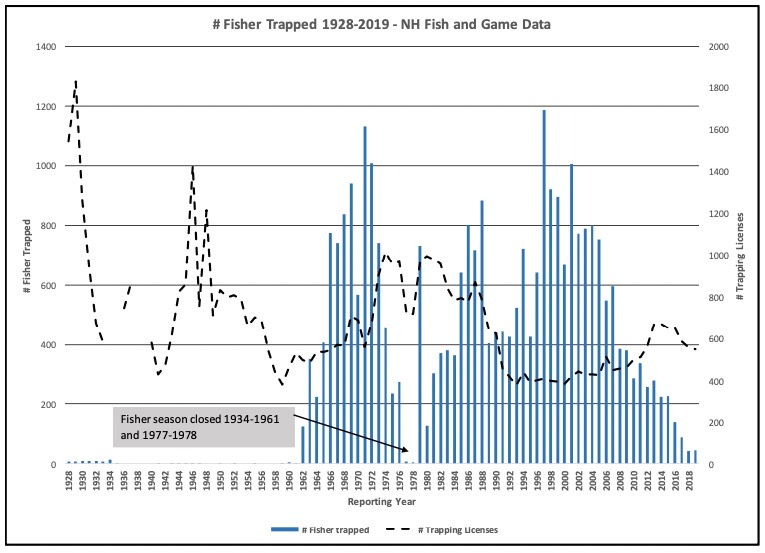

They say a picture is worth a thousand words. I believe the following chart tells the story of the failure to manage a healthy, sustainable population of fisher as required by statute.

This chart of fisher harvest (total number trapped) from 1928 to the present reveals substantial variability which appears to have an inverse relationship to the number of trapping licenses. More

importantly, these data show that the number of fishers were so low during two periods that the trapping season had to be closed. The fisher season was closed from 1934 until 1961. As the fisher population rebounded, the season was opened in 1961 and remained open until 1977 when it was closed again for two years.

Numerous examples of how management of fishery and wildlife resources without considering a “shifting baseline” has led to population instability and crashes. In fact, this appears to have happened with the fisher population in the late 70’s (See above figure). Ignoring the obvious trend of a declining fisher population, even more trapping licenses were sold during the late 70’s and the fisher population once again declined to a point where the season had to be closed. While current wildlife governance cannot be held responsible what happened 40 plus years ago, unfortunately this pattern appears to be repeating itself today and very little is being done about it. This outcome is not only a consequence to the fisher population, it also has ramifications to the entire ecosystem of which the fisher is a key component.

In the absence of any knowledge on what constituted a sustainable population of fisher, in the attached analysis I have assumed that the average harvest over the last 30 years would be a reasonable surrogate for a sustainable population. Based upon this assumption the most recent fisher harvest of 48 animals is 88% fewer animals than the lower 95% confidence limits of the mean harvest over the last 30 years. Based upon the trend in fisher CPUE and harvest data analyzed here it is apparent that the fisher population cannot support continued trapping pressure and be sustainable.

While there may be other uncontrolled variables, e.g., disease, weather, roadkill etc., that may help explain the apparent decline in the fisher population, trapping and hunting pressure are the only sources of mortality over which the Commission has some control, i.e. by closing seasons or adjusting bag limits. Using these management tools, in fact, is the primary means by which the Commission can fulfill its statutory responsibility of assuring a healthy, sustainable population of wildlife species. The Commission is well acquainted with the concept of adjusting seasons or bag limits to respond to changes in the abundance of other game species; whitetail deer, bear and wild turkey have been successfully managed to maintain a reasonably sustainable harvest over many years. Now is the time to apply these same principles to furbearers like the fisher.